Walking the Names

Walking slowly, reading, remembering, reflecting. Speaking the names of those who died of poverty in Bath Union Workhouse, buried in unmarked graves, unmemorialised. Walking with the toll of the bell that regulated their lives.

In the time of the virus, towards a wake and a memorial.

Officially forgotten dead and many others remembered .... we walk towards the site becoming a place of memory, reflection and kindness. A wildflower meadow.

In the time of the virus, towards a wake and a memorial.

Officially forgotten dead and many others remembered .... we walk towards the site becoming a place of memory, reflection and kindness. A wildflower meadow.

UPDATE and visit April 2024

A passing visit to the burial ground to pay respects to elders and voices past, present and emerging. The young trees have survived drought and other priorities, the single cowslip sighted in 2019 has been joined by the many survivors of two winters. A space finding its own presence again.

Bath Union Workhouse Burial Ground

read on to discover the story of the reclaiming of this site

|

opening observations as the project began

A field just off the Wellsway, Bath. A burial ground that does not exist on a current map. Here over 3100 bodies lie in unmarked graves, the last remains of those who died of poverty in the Bath workhouse between 1858 and 1899. In the low winter sun you can make out the mounds and depressions of the burials. A makeshift memorial comes and goes in a place that once may have had something more permanent. Visitors add flowers occasionally. |

|

A further 1100 bodies of those who died between 1838 and 1858 lie in unmarked graves in a small triangle behind the old Workhouse Chapel on Frome Road, Bath.

The only memorial there is to Rock 'n' Roll hero, Eddie Cochran, who died there following a car crash near Chippenham in 1960. Eddie's body was flown to the US and buried in California, three steps to heaven, with step one taken in Bath's former Workhouse. There were no memorials to the Workhouse dead. Until now. |

'Poor' Memorials:

from a small bunch of garden flowers to a wild flower meadow

A 'poor' memorial began where three old stones poked through the turf, perhaps traces of memorial to a priest who chose to be buried there. Here walkers paid their respects and acknowledged ancestors who had no choice, with flowers, stones and name flags. The memorial was renewed at each monthly walk. Today two yew trees are emerging, an official one and an unofficial one.

Walking the Names: an account of the project

Trees will grow and a wildflower meadow will bloom here. A place of memory and reflection is emerging thanks to the work of local residents, artists and descendants of those buried, unmemorialised, in unmarked graves. As the official memorial to a slave trader was toppled in Bristol, people in Bath sought to memorialise those officially forgotten. Neither of Bath Workhouse burial grounds exist on any modern map, there is no signage and until recently not even a plaque. Following a long campaign for recognition this is beginning to change. The autumn and winter of 2021 saw a series of planting events at one of the sites and a plaque was installed at this long overlooked and formally forgotten field.

|

Bath Union Workhouse still stands as grim and foreboding as ever, overlooking the UNESCO World Heritage designated city. The building established as a result of the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act was opened in 1838 replacing ‘poor relief’ provided by 24 surrounding parishes. The entire system was funded by a local tax paid by landowners, often the very same people who were then benefitting from their windfall share in £20m Government ‘compensation’ scheme for slave-owners. These tax payers were the same people who were memorialising themselves in the buildings and street names of the city and constructing the mythology of colony and empire. The same people who a generation or two before had enclosed the common land, pushing those who had worked on the land towards the city. Some of the elders buried in the Workhouse field and many whose remains are in the burial ground alongside the chapel came from rural Somerset, Wiltshire and Gloucestershire. The Workhouse warehoused those unable to be economically active, the very young, the disabled, the aged and infirm, all were punished, stigmatised for being poor.

|

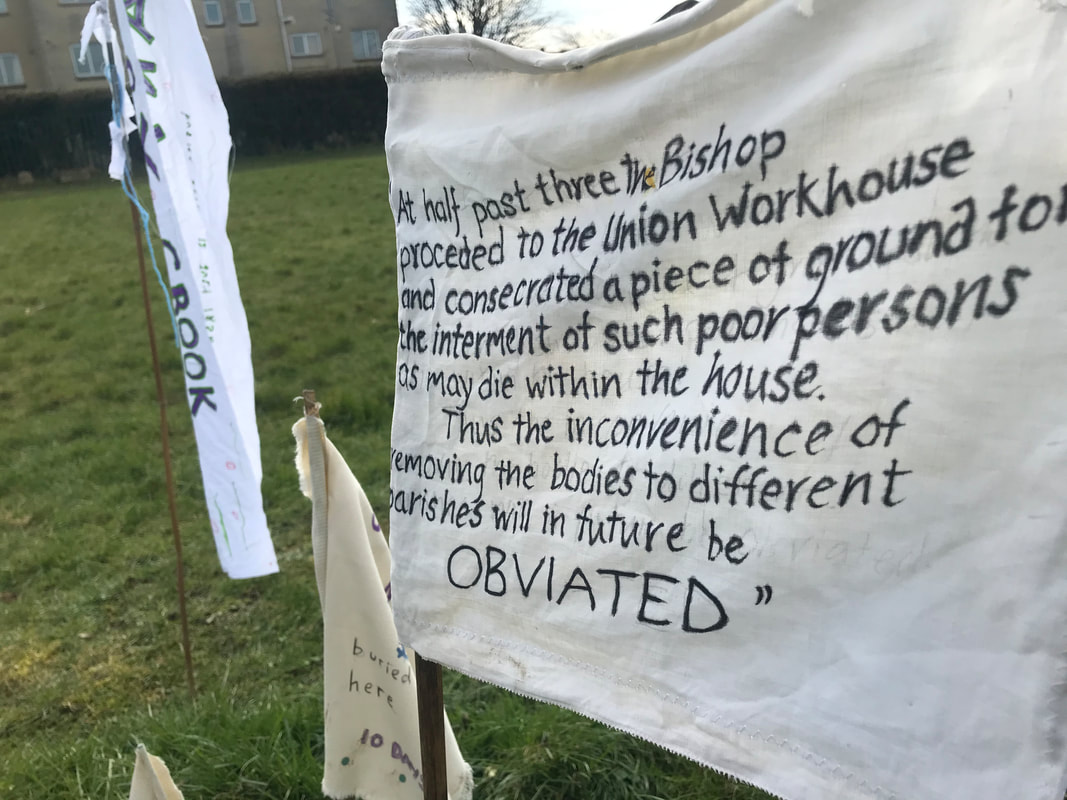

.That punishment continued into death. Instead of having the costs and trouble of returning bodies to their parish the Workhouse authorities bought and got the Church to consecrate land for burials. This was going on up and down the country, research by Bristol Radical History Group and the publication on the Eastville Workhouse (Ball, Parkin, Mills 2015) informed Walking the Names. Bath Workhouse has two burial grounds holding the last remains of over four thousand individuals, one alongside the chapel contains 1107 bodies and the Workhouse field where, between 1858 and 1899, over 3100 bodies were buried. The only memorial is to rock and roll hero, Eddie Cochran, who died in the old Workhouse building following a car accident in Chippenham. Cochran’s body, however, was flown to California.

|

In 2017 John Payne, whose great grandparents died in the Workhouse and were buried in the field, researched and presented an exhibition at the Museum of Bath at Work. Part of his research had turned up a diary for 1856 kept by the Workhouse Schoolmaster, William Winkworth. Winkworth led his children, mainly the boys, on many long walks including an epic 17 mile walk on a hot summer’s day around several of the northern parishes. Was this to tire the lively lads or to show them off to the parishioners or as some kind of performative warning? We don’t know, but this evolved into a cycle of public participatory walks hosted by John and myself. A closing walk to the burial ground coincided with the first Bathscape Walking Festival and has been associated with it ever since.

|

Following the 2019 Walking Festival Workhouse Walk I pledged to walk and read the names of all those buried in the field in the order of their burial. With Cochran’s hit ‘Three Steps to Heaven’ still echoing off the workhouse walls a slow walk seemed an appropriate approach. The project Walking the Names was a monthly slow walk across the workhouse field, participants walked as slow as they could taking turns to read names from the Workhouse register. The reading was paced by the tolling of the actual Workhouse Bell which I had recorded at the Museum of Bath at Work exhibition. This slow walking, reading and listening was a powerful experience drawing in other walkers and passers by. Each walk ended with a gathering, sharing, occasional poetry readings and discussion. You can still see the bell now silent, its clapper removed, silent on a wooden form in the foyer of St Martin's Hospital adjoining the old Workhouse site.

|

Monthly walks and readings continued as the virus struck. When gatherings were prohibited walkers continued and some recorded their readings, these were played back on the site and I edited these into a series of monthly videos. I subsequently produced a series of locative soundscapes on the Echoes platform, working with these readings and sounds. Download and walk the soundscapes from the links below. At this time walkers began to mark their presence and acknowledging ancestors by leaving flowers or some biodegradeable offering at a central point in the site. This point shown on the late 1890’s map of the site had a cluster of stones poking through the grass. In living memory this had been some kind of stone trough or table, a ‘home’ for childhood games of tag. It is possible that these stones are all that remains of a memorial to the Workhouse chaplain, John Scott, who in 1865 chose to be ‘buried with his flock’. This place where the old stones poked through became a gathering point and a place where the ‘poor’ memorial emerged

|

|

One spring day as the grass grew tall the memorial was completely scalped by the Council contractors’ mowers. The ‘poor’ memorial was back within a day and through into the winter it grew with larger and taller flags often flying the name of a particular individual. Each Walking the Names renewed the ‘poor’ memorial. As the death toll of the virus grew the walking became a space to reflect on those modern day deaths in underfunded care homes and the consider the legacy of the workhouse. Returning to walk together in late summer 2020 a set by a group of folk musicians, Bath City Jubilee Waits, gave the event a particular poignancy. Those buried in the Workhouse Burial Grounds were bundled into the ground out of sight. This was their final punishment. No final celebration of life.

|

Bath City Waits played the sound track for the wake the Workhouse dead were denied.

Through into 2021, Walking the Names continued completing the reading of all the names of those buried in the Workhouse field. A research group formed to flesh out the stories of some of those buried, one committed researcher, Aileen Thompson has made minibiographies of 48 individuals and is still going. These are available here. With news of a building development bid on the burial site beside the old chapel, monthly readings have continued there. Following further virus related delays and with the support of Bathscape and Odd Down Community Association the project evolved again towards making more lasting and sympathetic changes on the site. Bath and North East Somerset council who own the site agreed to some experimental changes in the mowing pattern and some new planting.

|

There was some guerrilla planting around the stones that poked through and in October and December 2021, the officially endorsed planting sessions took place, firstly wild flowers and then trees. The events were well attended and documented by a group of students from Bath Spa University. The plaque installed in October fell victim to trophy hunters but Bathscape on behalf of BANES Parks department renewed this and will be setting up an orientation panel for the site. Funding efforts continue to support a more formal memorial. The Workhouse field is still consecrated ground. Local residents hope to beat the developers and that the old Chapel might one day become museum and indoor space for reflection, respecting ancestors and considering the present.

Richard White April 2022 |

Soundscapes to walk with in the Burial Ground and on the Workhouse site:

Follow the links, download the files, walk and listen

|

Bath Workhouse Burial Ground: Walking the Names

As you walk in this space, listen..... Below your feet are the bodies of more than 3000 people who died of poverty in the Bath Union Workhouse between 1858 and 1899. There are layered readings from the Burial Register made during the virus lockdown, poetry from John Payne and perhaps some more. https://explore.echoes.xyz/collections/frZzWQxkxyJXa7VZ |

Bath Union Workhouse: a walk for the living with the route of the dead

Bath Union Workhouse had two burial grounds...this sound walk is an invitation to follow a route between the two burial grounds and two different journeys. There is music, poetry and information. https://explore.echoes.xyz/collections/U0Pfiy2DKzgeFk1f |

The soundscapes are locative audio pieces, designed to be listened to on headphones whilst walking on the site. Follow the links above to download the Echoesxyz app and the audio files.

You can listen to the podcast episode below anywhere! Scroll down for videos made during lockdown.

You can listen to the podcast episode below anywhere! Scroll down for videos made during lockdown.

More sounds from the Burial Ground:

Walking the Names and the story of the Bath Union Workhouse Burial Ground was featured in the March 22 Bathscape podcast, Footprints.

|

BBC R4's Open Country visited the burial ground in April 2022 and devoted a whole show to the project, follow the link to listen on BBC Sounds: BATH WORKHOUSE BURIAL GROUND |

|

Workhouse Walks

A series of performative walks in collaboration with historian and poet Dr John Payne linked to his 2017 exhibition about the Workhouse at the Museum of Bath at Work. We learned about the Workhouse school and the love-struck school master walker, Mr Winkworth, The Workhouse Walks opened conversations about poverty and welfare. There were further walks to the burial ground in 2018, as part of the Bathscape Walking Festival where we improvised a poor requiem in the rain. Paying our respects to the forgotten poor of the enchanted city. More about the 2017 walking project here. This was our first encounter with members of the Bath City Jubilee Waits, a band who were later to provide the music for the wake the workhouse dead never had, the culmination of the Walking the Names project. The resonances from these walks continues, opening conversations on poverty, welfare and civic responsibility. Many questions are unanswered about who the dead were and where they came from, as well as the practicalities of their burials and how this space might memorialise them appropriately. On the Workhouse Walks we retraced the epic walk Mr Winkworth had led the boys of the insitution on around the parishes of Bath. Perhaps here lie their parents or grandparents, perhaps some of the boys themselves.

John Payne's research on Bath Workhouse is available to download below

We are beginning to learn more about those whose remains lie under the soil of this field behind a grim wall just off Bath's Wellsway.

|

An aerial photo a hot summer ago faintly shows the ragged teeth of the burial plots jammed in over a period of forty years.

Here in this field a rich city in a rich country at the centre of the richest Empire dumped the bodies of its poor.

The dead were officially and punitively denied the dignity of a 'decent' funeral, bodies were taken in a tunnel under the road and buried behind high stone walls. The authorities were consoled that at least they were buried in consecrated ground. The ground is still consecrated. Bath and NE Somerset Council own the site and still cut the grass. Bath Parks department have advised and now provide sensitive ground maintenance. Bathscape support has been amazing with more to follow and we are grateful to be supported by Bath's OddDown Community Association | ||

|

An evolving project

By 2019 the names of the Workhouse dead had been digitised we now at least had the names from the old register. This opened up a far easier way of finding out more about them. At the end of the year John Payne and I hosted the first slow walk, walking and reading out the names, day by day, week by week and year by year of their burial, accompanied by a recording of the Workhouse bell, tolling This continued throughout 2020 on the first Sunday of the month. There were moments for sharing and conversation at the end of each walk, developing a continuing improvised memorial and poor requiem. In April 2020 as a result of virus restrictions this part of the project went online, returning to the site initially as a socially distanced walk.

After more than a year of walking, reading and questioning and slow listening to the names of those buried in the field and the thoughts evoked, the final slow walk for Walking the Names took place in April 2021, a further gathering took place as part of the Bathscape Walking Festival 2021. In the autumn planting for the wildflower meadow began. The site evolves, a place of memory, kindness and reflection emerges.

|

Walking conversations and research

If you would like to be involved in taking this project further, help network, fundraise or research or have information to add come please use the contact form below and become a friend of the Workhouse Burial Ground ( it still needs them!) |

Walking the Names in the time of the virus

|

April 2020, as Covid-19 closed us down to isolation and social distancing, Walking the Names went online. An informal trawl of those who had joined the first few monthly walks resulted in nearly twenty walkers interested in taking part on line. Each walker was issued with a set of names from the Register of Burials at the Bath Union Workhouse burial ground.

Our first virtual Walking the Names on Sunday April 5th was the day in which the government announced 708 dead from the virus. In May as the UK deathtoll from the virus officially reached 30000 the project continued. The June walks took place as the death toll exceeded 40,000. Many of the deaths were in carehomes, the modern homes of the old and the vulnerable, many of the deaths are of careworkers. There are resonances with those who died of poverty in the Victorian Workhouse and we reflect on contemporary responsibilities. Every names was a life. Every death a local tragedy. Walking and reading the names, recorded or not, breathes a momentary presence to that life.

As we walk and read, connections emerge.

Walkers have discovered ancestors buried in the field. Tragic local stories, snap shots of brutal poverty and brief lives before the welfare state, glimpses of the punitive regime of the workhouse. Respecting the lockdown restrictions walkers were invited to walk alone, reading the last set of names from the Workhouse Burial Register. I walked with these edited recordings from the Burial Register from other walkers and a recording of the workhouse bell tolling. These were subsequently edited with other field recordings into the two Echoes soundscapes linked here |

This column of the page records the individual walks and readings taken in our permitted moments of exercise, I have assembled them with imagery from the walks and layered the voices to produce short audio-visual memorials.

These assemblies of readings retain the noises, distortions and reader stumbles as sound echoes of our reaching out through time, shame and the Burial Register to real lives lived long and others so sadly cut short.

|

|

A walker shared a poem....

WALKING THE LOST I walk in circles on the lawn just as I’ve walked the distant hidden burial ground. I read my list of names just twenty of the twenty four hundred hidden from history below the soil there. Unmarked, they have vanished, as tears vanish, into the earth. Twenty names with life spans varying from twelve hours to eighty six years. The world around me is locked down in pandemic. But would we let those dying now disappear without trace? I read the names with pride proud to help them resonate even quietly and quickly across this earth, once their earth. Able Lawrence 5th April 2020 The garden of Westfield House, built in 1721, looking across the valley to the city of Bath. I often think of what this house and all the people who have lived here, have borne witness to - the times they lived in - the lives they lived here.

Other walkers are trying to discover some more about the names, their stories and how their lives ended hidden from sight, buried in an unmarked grave. In the absence of photographs others are trying to imagine their faces. More readings and information to follow. In the time of the virus this was a way of connecting, bearing witness, walking and asking questions.

|

Walkers shared images of where they walked, where they read; contributions came from far and wide, from Denmark and Frome and the Burial ground itself. Walking in witness and with solidarity, spring time in the year of the virus.

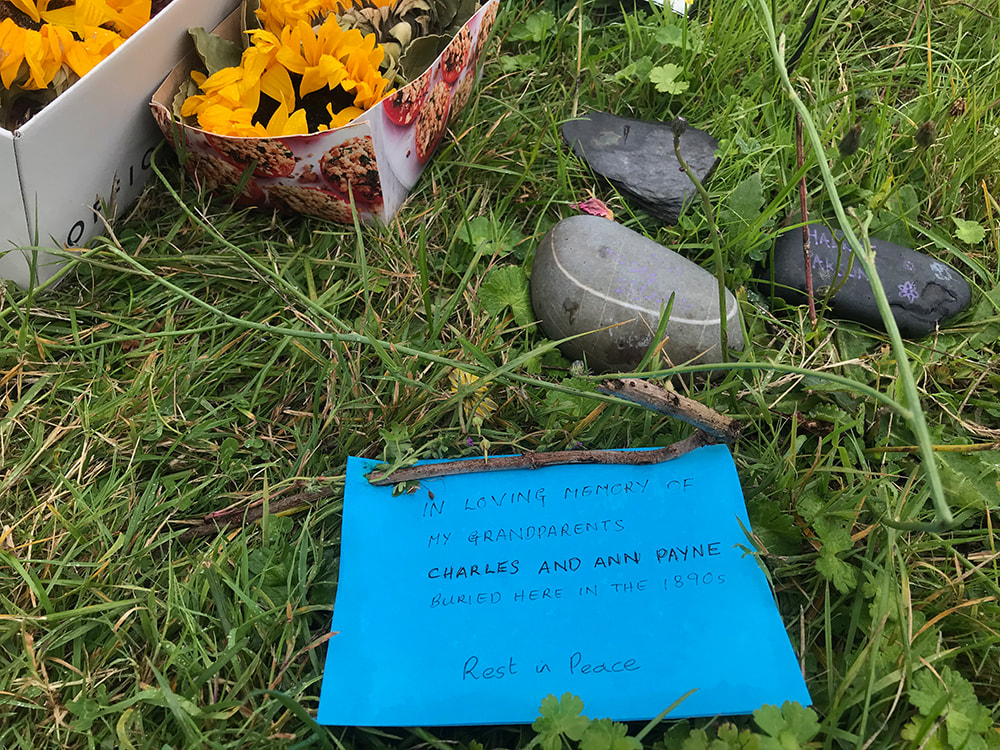

John Payne shared a story from his family:

My great-grandfather Charles Payne was born in 1829 in Chewton Mendip, one of a family of 9 brothers and sisters. In about 1850 he went off to Bath to make his fortune, marrying Ann Phipps there in 1853. He worked as a gardener, but was unable to make provision for his old age. Both he and his wife died in the workhouse and are buried beneath the field at Odd Down. There are records. Their names are there in the list of burials carefully preserved and transcribed in the Bath Record Office in the vaults of the Bath Guildhall. And there is some interesting medical material too. It appears that Charles Payne was one of the noisier inmates of the Bath Workhouse. In fact he was raving. On 1 July 1891 he was admitted to the Mendip Asylum at Wells. His medical certificate from the workhouse reported: ‘he has delusions, viz that he has a million of money in Chancery and 40 acres of land at Highbridge which is not correct. He is very destructive, tears up the bed clothes and is very noisy. History – has been in the workhouse for some years but his mind has only been affected for about 3 months. No personal history available.’ To have ‘money in Chancery’ implies some kind of unclaimed inheritance, and this sense of having been badly done by may well relate to the decline of the Chewton Mendip family from tenant farmer to farm labourer status in the first half of the nineteenth century. Charles’ occupation on admission is ‘farm labourer’. There is no record of any connection with Highbridge, a town on the Somerset Levels, well distant from Chewton. John Payne, A West Country Odyssey, Hobnob Press, 2020 (forthcoming) Another walker was working on the recording day in April, he wrote,

By chance I'm on duty today so this was recorded on a break walking the grounds of Dorothy House Hospice: to me there is a contrasting continuity there. I needed to update my team on a few things today and talking about your project as a way of highlighting how important it is we keep going at this time. By keeping this history alive it has reached into the present day corona virus response in a way that would have been impossible without your efforts so thank you! |

Return to the Burial Ground

|

Some walkers continued the regular walk in the burial ground. We tested a socially distanced walk reading the names to the sound of the Workhouse Bell. This proved to be a moving and powerful experience reading and walking together, sometimes just listening,

sometimes reading, walking and moving sometimes just being in the space. Regular mowing of the entire site by the Parks Department had slowly been erasing the remains of an old memorial. Each time we walked we left flowers and finally the memory space has begun to gather some respect. In July 2020 with the intervention of Bathscape a new mowing pattern was agreed, the mowers left the space allowing our 'poor' memorial to evolve and emerge.

On Sunday 6 September 2020, walkers were joined by Bath City Jubilee Waits. Their set included some sad tunes and some more cheerful sounds that might have been heard at a village wake. See the video at the top of the page or view it directly here

The Waits were to return for a closing gathering for the walking project a year later at the end of a Workhouse Walk hosted by John Payne and myself for the 2021 Bathscape Walking Festival. The Bath City Jubilee Waits originated in the 18th century. The original City Waits provided music on civic occasions. The Jubilee Waits were set up in the jubilee year of 2012 with the patronage of the Mayor of Bath to do the same. The Waits play music in the traditional English style, and are dedicated to the idea that such music should be lively, spontaneous, and enjoyable both to play and to listen to. Find out more about the Waits here |

Reflections and Research

|

Aileen Thompson is a regular walker and contributor to the research. She has been digging in the archives getting beyond the names and dates in the burial register. She has discovered countless local tragedies and mysteries such as the story of Luke Shewring in the right hand column.

Aileen began trying to track down some of the many children buried under the Workhouse field. Many only a few days or weeks old, she found very little but other names caught her eye, Luke's story is just one of them. Somewhere near here Luke's body and on some days several bodies would have been trundled on a trolley though a tunnel under the road towards the workhouse fields and the burial ground. Once inside the Workhouse inmates lived in a world surrounded be grim dark walls, effectively they were disappeared.

Stories of the names:

In August 2020 we walked with and read the name of those who were buried in 1871. Walkers had started to bring small flags with the names of one of those buried. I read the name of a boy who was the youngest buried that year, Henry Wilcox, buried on the 27 May 1871 aged but two days, I wondered how few times his name would have been called out in his short life. Aileen called out the name of Jane Dunk the oldest to have been buried that year on the 10 April 1871, she was eighty nine years old. Aileen had done some research to find a bit about Jane's back story. Jane was married at 20 and a single parent within a couple of years as her husband died. The next twenty years of her life are a mystery but life must have been very hard bringing up her daughter. She married again in her late forties but her new husband a quarry worker was not to accompany her into old age. He died and Jane went into the workhouse where the continued to work in the laundry and as a servant. Worn out she died and was buried in the burial ground. |

WALKING THE NAMES - 2 - LUKE SHEWRING My house is built where part of the Workhouse used to be, every day I see the remaining Workhouse buildings, now turned into flats, or part of St. Martins Hospital. It is hard to imagine what life must have been like for the inmates of the grim Workhouse. Luke Shewring was one of these people, his name mis-spelled on the Workhouse Burial Register as Luck, precious little of that in his life. Luke was born in Lacock in 1803. He was a labourer, moved to Bath to find work and, in September 1827, married Ann Rice in Walcot. They had six children, moving house every two years, a good indicator of poverty. In the 1841 Census they lived at 10 Hat and Feather Court, Walcot. After this Luke disappears for the next thirty years, although his family are in the 1851 and 1861 censuses, Ann claiming to be married. Where was Luke during this time? Working elsewhere? In prison? Had he abandoned his family? None of these explain why he is missing from those two Censuses, he should be there somewhere. Perhaps he was there, living with his family, hiding on Census Day so as not to be counted. Was there a financial benefit in doing so? Luke reappears in the 1871 Census, taken 2 April, as an inmate of the Workhouse, claiming to be married. Ann is also there, still living in Walcot, for the first time claiming to be a widow. Luke did die that year, but not until July. He is just one of the forgotten people who have become almost as real to me as my own ancestors. When I “Walk the Names” on the first Sunday of each month, the names resonate in my mind. Who lies under the grass on which I stand? They deserve to be known, my part is to try to raise awareness of their existence. Aileen Thompson June 2020

More details on Jane Dunk below, as Aileen says,

The story of this family is a sad reminder of how poverty can continue from one generation to the next, and how men, desperate to feed their families, can be pushed into a criminal act, and have to pay the price. I had wondered why none of the children had helped their parents when they needed it. The simple fact is they couldn’t. They were either in the same desperate condition themselves or they were living too far away to have knowledge of what was happening back in Bath.

View more of this research on the stories behind the names here

| ||||